Highlights

- Parental separation decreases child educational attainment, regardless of the child’s genetic predispositions. Post This

- Children of parents who separated before they were 18 were less likely to obtain a college degree and attained fewer years of education than children of intact marriages, regardless of genetics. Post This

- Children of college-educated mothers with a low predisposition for education were much more likely to obtain a college degree if their parents stayed together than if their parents separated. Post This

My sister and I have had very different lives. Despite the fact that we have the same mother and father (and share, on average, half our genes) and the same upper-middle-class family background (our father was an Australian doctor and our mother had a college degree), she had no education beyond high school, and her life has been characterized by drug use, abusive relationships, and criminal activity. I, on the other hand, earned my Ph.D. and became a college professor, got married, and had two children (and now one grandchild).

As a sociologist, I know that statistically the children of divorced parents generally have worse outcomes on many metrics, and so I have wondered whether things would have turned out differently for my sister if our parents had stayed married. Our parents were divorced when we were both very young (I was about 6 and she was about 2), and my sister and I were raised by our father and two consecutive stepmothers. I have discussed this with my sister and whether things would have turned out differently for her if our parents hadn’t divorced, but she assures me that this was unlikely, adding, “I was never good at school.” She believes that despite being sisters, we are different people and that is why we have had such divergent lives.

Social scientists know that individual genotypes do play a role in individual life outcomes, as well as individual circumstances. It is possible that the negative effects of parental divorce on child outcomes are not only due to the divorce itself, but (at least partly) due to shared genes between parents and children. This has been argued by many, including the conservative commentator Richard Hanania, who wrote: “The reason there's a correlation between broken homes and bad outcomes is primarily genetic.” For example, the fact that children of divorced parents are more likely to exhibit depression than children of intact marriages may be because people with depression are more likely to divorce, and their children are more likely to be depressed, not because of their parents’ divorce but because they inherit their parents’ genes for depression. Further, individuals differ in the genes they inherit from their parents; for example, some people inherit a lower genetic propensity for education than others. That is, my sister’s low level of educational attainment may be because of her unique genotype (as she herself suggested) and may not have been influenced by our parents’ divorce.

There are analytic techniques that allow us to examine how much of a particular outcome is due to individual genotype and how much is due to particular life events. For example, a new paper in the journal Demography examines how a child’s educational attainment is influenced by both the child’s genetic predispositions toward education and the parents’ marital stability. This research used two high quality U.S. data sets that have information on both a child’s genotype and a child’s education and family history—the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (AddHealth) and the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). Past research has shown that parental separation and divorce have a negative effect on children’s educational attainment, particularly for children from high socioeconomic status (SES) backgrounds who otherwise are more likely to attain high levels of education. In populations of European background, past research has also shown that there are specific genetic indicators (sets of genes measured with polygenic scores) that are associated with an individual’s educational outcome.

This research gives new evidence that it is parental separation in and of itself that decreases child educational attainment, regardless of the child’s own genetic predispositions for education and other factors associated with less education such as depression, neuroticism, and ADHD.

In their new study, demographers Fabrizio Bernardi of the National Distance Education University (UNED) in Spain, and Gaia Ghirardi at the University of Bologna in Italy were able to determine how much of a child’s educational attainment (college degree and years of education) is explained by their genetic predisposition toward education (their educational polygenic score) and how much is explained by their parents’ marital stability (measured by whether or not their parents separated before the child was 18). They also look at the effects of parental socioeconomic status (measured as whether or not the mother had a college degree) on the educational attainment of children.

First, they find that children of parents who separated before they were 18 years old were less likely to obtain a college degree and attained fewer years of education than children of intact marriages, regardless of their genetic propensity for education.

Second, they find a larger negative effect of parental separation on educational attainment for children from better-off families, as previous research has found.

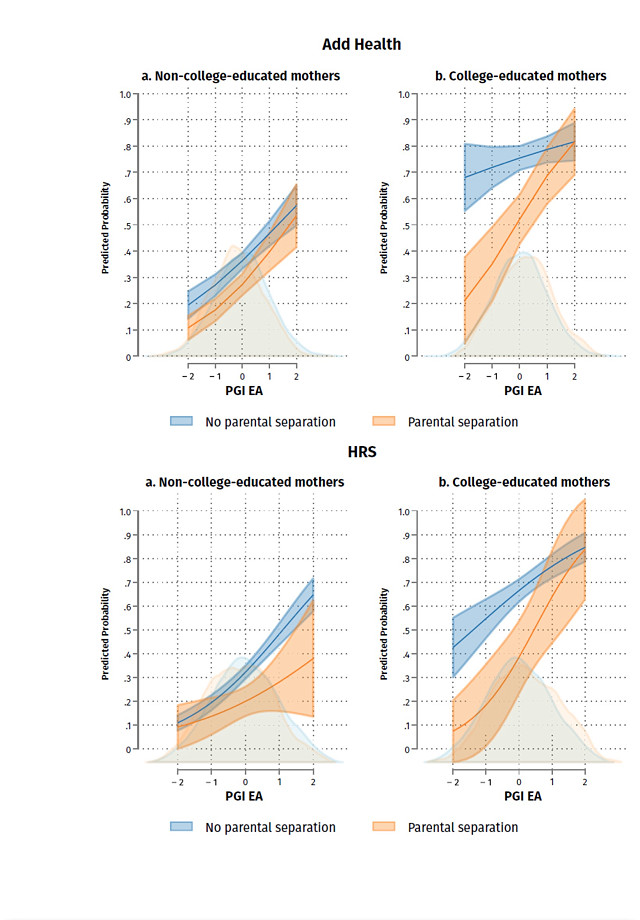

Last, they find the negative effect of parental separation on educational attainment was greater for children with a low genetic predisposition for educational attainment, particularly for children from higher SES backgrounds (see Figure 4 from the paper below). So children of college-educated mothers with a low predisposition for education (as measured by the child’s polygenic score) were much more likely to obtain a college degree if their parents stayed together than if their parents separated. For children of non-separated parents in better-off families, obtaining a college degree was largely independent of their genetic propensity for education. This suggests that parents who stay together are better able to compensate for their children’s low genetic propensity for education than parents who divorce.

Figure 4. Predicted probabilities of college completion by parental separation, mother’s education, and PGI EA with 95% percent confidence intervals and distributions of PGI by mother’s education

Note: These figures show predicted probabilities from postestimation margins based on logistic regression. Sources: Add Health (N = 3,341) and HRS (N = 2,506). Higher PGI EA scores mean greater propensity for education.

Because divorce is associated with genetic factors such as depression, neuroticism and ADHD, and these genes may be inherited by children and influence their educational attainment, the researchers also controlled for the child’s polygenic scores for these traits. They found that despite these controls, parental separation still negatively affects a child’s educational attainment. In particular, children from high SES backgrounds with low polygenic scores for education were significantly more likely to attain a college degree if their parents stayed together than if their parents separated—again regardless of their genetic predispositions toward depression, neuroticism, and ADHD.

This research gives new evidence that it is parental separation in and of itself that decreases child educational attainment, regardless of the child’s own genetic predispositions for education and other factors associated with less education such as depression, neuroticism, and ADHD. In particular, this paper shows that high SES parents who stay together can help compensate for a children’s low genetic propensity for education and are better able to help their child attain a college degree.

This suggests that even if my sister does have a low genetic predisposition to education, if our parents had stayed together, she would have been more likely to continue her education in some way and perhaps steered clear of other high-risk behaviors. This, in turn, may have helped her avoid some of the adversities she has experienced in her life.

Rosemary L. Hopcroft is Professor Emerita of Sociology at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. She is the author of Evolution and Gender: Why it matters for contemporary life (Routledge 2016), editor of The Oxford Handbook of Evolution, Biology, & Society (Oxford, 2018), and author (with Martin Fieder and Susanne Huber) of Not So Weird After All: The Changing Relationship Between Status and Fertility (Routledge, 2024).